Welcome to Tune Glue, a newsletter that’s run in conjunction with Tone Glow. While the latter is dedicated to presenting interviews and reviews related to experimental music, Tune Glue is a space for interviews with artists of any kind. These interviews could be with filmmakers, video game designers, perfumers, or musicians who aren’t aligned with what Tone Glow typically covers. Thanks for reading.

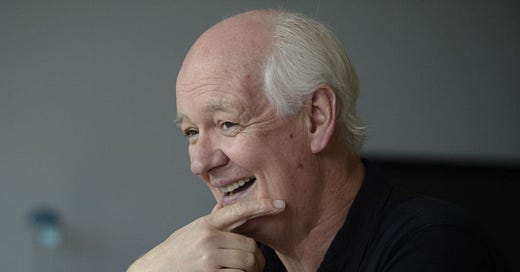

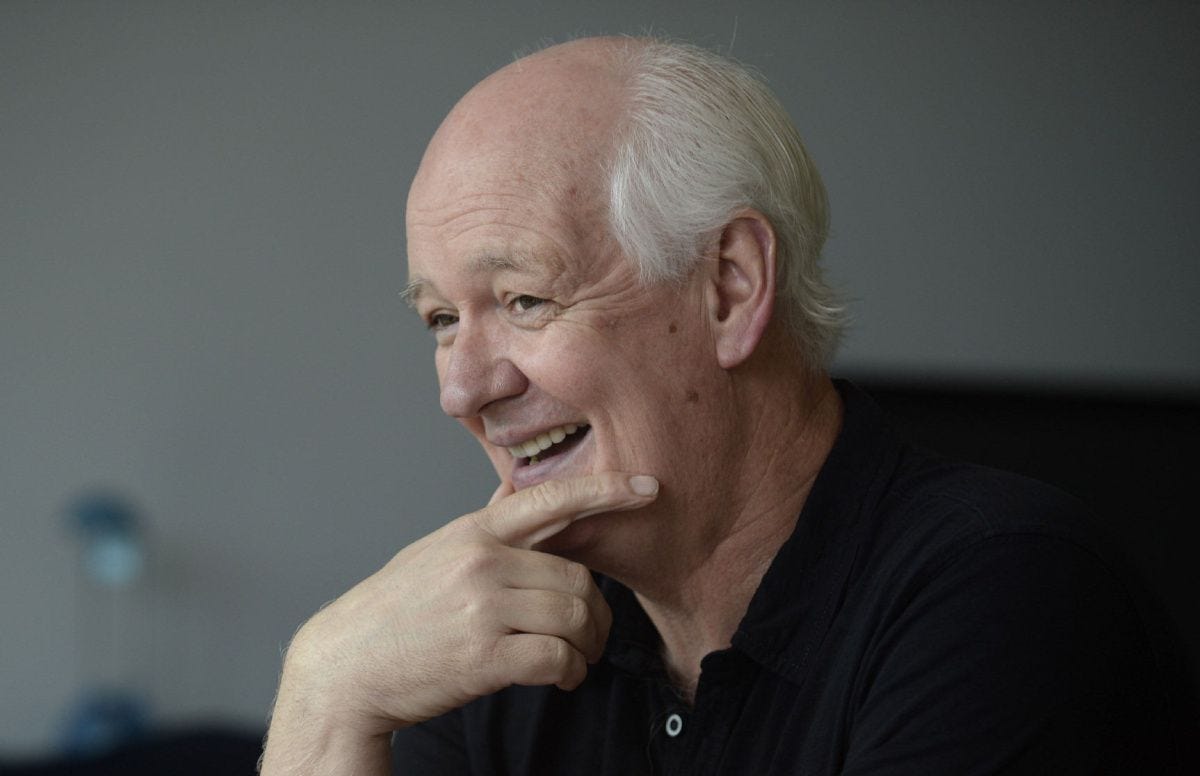

Colin Mochrie

Colin Mochrie is a Scottish-born Canadian actor, writer, producer, and improvisational comedian who is largely known for his appearances on both British and US versions of the television show Whose Line is it Anyway? Since 2002, Mochrie has performed a two-man show with Brad Sherwood and, more recently, has done shows involving a hypnotist called Hyprov. Mochrie recently starred in a summer camp film called Boys vs. Girls. Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Mochrie on December 22nd, 2020 to discuss his family, summer camps, the way improvisation has impacted his real-life relationships, and more.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hey Colin, how are you?

Colin Mochrie: I’m good, how are you?

I’m good! I’m a high school teacher and we just had a meeting via Zoom to discuss the next semester. So that’s been my morning.

Where are you?

I’m near Chicago.

How is it there?

There was a point a month ago where Illinois was the worst state in terms of increasing number of COVID cases. I don’t know if that’s still true but just in general, it’s upsetting to think about how there doesn’t seem to be an end in sight to all this.

(sighs). Yes.

How about you?

I’m in Toronto and we’re going into lockdown on the 26th. We’ve had a bit of a spike but hopefully people will do the things they’re supposed to do and we can get back to some sort of normal life.

Has the year been okay for you?

Yeah. You know, you hate to talk about positive things when a pandemic hits but right before everything went really bad, I was in Utah. I was in the middle of two different tours—one with Brad Sherwood and one with a hypnotist. And I was also shooting a movie. I was going from all of that into suddenly being in the vulnerable group of a pandemic. I came home and… it’s been good.

I always thought, “I don’t think I can retire.” And this pandemic showed me that maybe I could. This is the longest I’ve been home in, literally, 18 years. It’s been nice reconnecting with my wife and my daughter moved in with us right before this all happened so she could save some money to get her own place. I’m sure it’s the same as in Chicago where the rents are just insane. So that worked out beautifully. It’s been fairly stress-free. It certainly helps being trapped in a place with people you love (laughter).

I wanted to start talking with you about the earliest parts of your life. I know you were born in Scotland. When you think about your time being there early on, do you have any specific memories that come to mind? I know you were super young then.

Yeah, I moved when I was six. I mean, my parents did but I just went along with them (chuckling). I actually just reconnected on Facebook with my first girlfriend, Mary Brown. And you can’t get a more Scottish name than Mary Brown (laughter). I have vague memories of places. My grandparents I remember very strongly—they would come to Canada every year. Going back now, I love Scotland. I can see how it was a big part of my upbringing. When Scottish people leave Scotland, they take it with them (laughter).

My father was a rare Scot in that he wanted to go elsewhere to make life for his family. He didn’t seem to have the sentimental attachment to Scotland like most people do, but in our house we had velvet paintings of pipers and there was bagpipe music all the time, so obviously there was still something there, but he did love Canada.

But I love going back to Scotland now. I see where parts of my humor developed because they’re very morbid people. They’re constantly talking about death. Whenever I call my mother, the first thing I hear about is everyone who’s dying or dead (laughter), whether it’s a celebrity or someone who I don’t know. I get the death news out of the way and then it’s like, “Okay how are you doing?” I certainly have that in me, so Scotland is to blame for that.

Do you know when you recognized that you had that Scottish humor? That it was a part of you?

It probably wasn’t until I started doing comedy regularly and then looking back I thought, “Oh, I’ve always been kind of dark.” It’s just that I’d never exposed it to an audience and you get the reaction from them like, “Oh, that’s dark” and you go, “Oh, that’s been a part of my life forever—I just accepted it.” Nobody mentioned anything. Nobody said “Boy, you’re dark.”

Do you remember instances of you being or saying things that were dark—as a child, before you went into comedy?

You have to remember, it was a long time ago, Joshua (laughter). A lot of those memories are gone forever. But no, I can’t remember any specifics. I was always a pessimist. Well, I’d prefer to think of it as a realist. I was always prepared for something bad going wrong. I never wanted it to happen, but I always wanted to make sure, “Okay, when this happens, this is my avenue, this is what I can do.”

My wife is an incredible optimist, but I always find when things go wrong, they hit rock bottom so much quicker because they have no fallback plan. It’s like (in a frantic, worried tone), “What the, but this wasn’t supposed to happen!” “Well, follow me, I’ll take you out of this.”

I’m glad to hear about your wife being a strong optimist.

Yes, amazingly. God bless her.

Would you say you were close with your family growing up?

Mmm… no. We were a very Scottish family. The kids were sort of seen, not heard. They were very old school with discipline. They never hit us, but there were threats. There was never any spanking. My father was quite imposing and had a very loud voice. I never heard him whisper (laughter). Always very loud. And so that tended to make me quieter. A couple years before he died he had a stroke, and one of the byproducts of that was that he became very emotional and much more open than he had been. So in the final years we became much closer.

My brother and I are close. My sister and I have a 14-year gap so I was out of the house when she was growing up. We’re not strangers or anything—I like my family. But my wife Deb, her father was one of 14 and her mother was one of 8, and I still don’t know the names of everyone in her family, and we’ve been married 32 years. Her cousins are like brothers and sisters to her and she’s in contact with them. She’s one of those people who’s in contact with all her high school friends and her best friend is someone she’s known since 4. She’s one of those people—so unlike me (laughter).

I’m glad you were able to connect with your dad on an emotional level.

Yeah, me too. And especially as I’m getting older—I mean, every day now I look in the mirror and go, “It’s my dad!” But through that I learned, in using him maybe as a bad example (chuckles), about relating to my daughter. I knew my parents loved us but I don’t think that was ever said at all. So when we had our daughter, my thing was, “I’m telling this kid every day that I love them” and I’m certainly much more open than my parents were. So that’s been good.

Was that hard for you to do, to be more open with your daughter?

No, not at all. It was probably one of the easiest things. The minute she was born it was like, “I’m in love again.” And I would still do anything for her. She’s just amazing. She was the easiest kid—she would sleep through the night really early, she would wake up in a good mood all the time. It was like, “Okay, we can’t have any more kids because there’s no way this will happen twice in a row.”

Right. Wow. With you sharing these stories about your parents and yourself, and then with you and Deb with your daughter… something I reflect on is the ways in which I’ve “inherited” traits from my own parents just from living and having grown up with them. Do you feel like you’re similar to either your father or mother in certain ways that are impactful to how you live your life?

(pauses). I gotta say, these questions are great because I’m actually having to think, which I don’t usually do. I was similar in some aspects to my father, but not a lot. He was adventurous. Like, he moved to Canada with no support system because he had this idea of what he wanted to do. When I decided to become an actor, my mother would send me—and for years afterwards—matchbook covers that said “You can be a lawyer” on them (laughter).

My dad, from the very first day—and although he had no real concept of what theater was—said, “You do what makes you happy. If that’s making you happy, do it. I wish you success.” In that way he was quite open. He really wanted his kids to do whatever made them happy. I think I got that from him. My mother is a real worrier. I don’t have that—I have more of my dad’s thing where it’s just, “Let’s see what happens, it’ll work out.” And that’s a pessimist talking (laughter).

I’m so happy that your dad said that to you. What a beautiful thing.

Yeah, although to be fair (laughs)—and it’s all true and he totally supported me and when I made it, no one was prouder—but when I was in theater school, he would come see me and at every show he’d bring a newspaper just in case he got bored (laughter). So if I ever heard a rustle of a newspaper I thought, “Damn, we’re losing him!” (laughter).

Was entertaining him your main priority? Was that who you cared about entertaining most?

I mean, certainly when they came to shows I wanted them to enjoy what I was doing and to see that I was making the right choice. And I still do—I hate when friends and family come to shows that I’m in because it just adds another pressure. You always get the calls, “Oh, can I get tickets” and you’re trying to figure out if they got their tickets and if they’re there. One of Deb’s cousins might bring a new girlfriend so I have to try and impress them. That’s why I love touring—there’s no one you know in the audience and it’s much more relaxing.

To bring this back around to your daughter, I want to ask: What do you see in your daughter that is greater than yourself? What’s she capable of doing—what have you seen from her life—that you feel like you wouldn’t be able to do?

Oh, she has so many things I don’t have (laughter). As a parent, you want your child to be better than you. My daughter has always been very open with us. She’s always been very curious. She’s always been curious about sex. It was one of those things where it was like, “We’ll talk to you about that, but you’re five (chuckles) so we don’t feel that you have the emotional maturity—and Dad doesn’t have the emotional maturity—to talk about this at this point.” There were times at dinner where she was like, “Can we talk about fellatio?” and I’d be like (in a nervous tone) “I just want to finish my burger.” (laughter). “Let’s move this to a little later. We’ll get to all this.”

She’s an activist, she always was. As a little kid, she was always looking out for the underdog. She was the one where, if a new student came to class, Kinley was the first one there helping them navigate through the school, meeting people. She and my wife are members of the United Church. She, with a couple of the other kids there, started a thing called “Out of the Cold” where they go to shelters and dish out food and talk to people.

So she’s always had a strong social awareness, and especially since coming out as trans, all of a sudden we’ve become the experts—people come to us and ask for advice—but she’s always there to come and talk to them. She has a great way of saying things so no one is threatened or feels stupid. She gets to the crux of whatever the problem is and solves it. She’s amazing. She could clean up her room a little bit more, but aside from that… (laughter).

That’s all really nice to hear. And it’s always beautiful to hear this sort of intergenerational dialogue and learning. It’s not something you hear about often.

Yeah, when it comes to the area of sex, I’m still waiting for my parents to tell me anything about it (laughter). I had to learn on the streets, where all the good information was (laughter). All of the problems of today’s world is through ignorance, and if we could teach people about sex or however politics works or what happens if you lose an election (chuckles)—those kinds of things—problems would be solved if we’d come together more easily.

Deb’s family—the immense family I talked about—is all very conservative. So with Kinley’s transition, Deb and I thought it was going to maybe be a bit of a rocky patch. They were incredibly supportive of Kinley, and it’s because they know her—they know who this person is—that it was easier for them. And then they started reading up about it, and then that gave this pessimist a little bit of hope, thinking, “Well if these people, who are very conservative, can take something that is so outside their realm of understanding and try to understand it, that’s a good thing.”

You mentioned how your family is part of a church. My understanding of the comedy world is that it’s not the most progressive. I’m also thinking about how it’s the same for churches too—well, obviously churches are all different, but generally speaking they’re not—so I’m wondering how you’ve navigated and approached these different topics within these spheres of your life.

My thing is that I research and try not to make snap judgments. It’s hard. I think as human beings that’s just what we do. And of course when you’re researching, you sometimes go to the research that’s more in agreement with how you feel without looking at the other side. But it’s all about educating yourself.

I mean, I’m not a staunch churchgoer, my participation in that is that I’m the Star of Bethlehem at the church concert (laughter) and that’s it. Deb is very involved—she’s in the choir. Kinley has moved away a little bit but she still… (chuckles) I just remembered a story about her. When she was about eight, she said, “I think I’m Jewish” and I said, (in a perplexed tone) “Really? Why is that?” “Well I don’t believe Jesus was the son of God, I just think he was a guy.” And I said, “Oh, let me just say you’re not Jewish because there’s a whole other side that you’re missing.” Or whatever! And it’s something we talk about because we have different views.

I’m of the belief that the Bible is, well, a good book, to start off. There are things that seem to get lost when “fervent” Christians talk about the Bible. Things like “love your neighbor” seem to be the first thing that’s tossed away, but to me that’s the most important thing. It’s the golden rule. Do unto others as you would have others do unto you. It’s common sense and teaches about decency, and people have a way to twist the words to fit their own agenda. I just don’t understand how religion became a club where, if you’re not in it, you’re damned for all eternity, instead of being like a school.

I have friends who are Catholic, Jewish, Christian—all different faiths—and I admire people who have that faith. I admire people who have that belief—almost like an optimist—because I really don’t. I would never denigrate anyone who does, especially anybody who uses that belief in a positive way and uses it in the way it’s supposed to be used. I really admire that. I admire people who embrace all the Christian values where, “Yes, this is what it should be.” Boy, this is a rambling answer (laughter). I actually forgot what the question was, I just thought, “Keep talking and it’ll come back to you.” (laughter).

But yeah, in improv, we tend to stay away from the controversial things. Not that we would do hard-hitting political improv—our stuff would be, “Oh, he’s dumb” (laughter)—but we found that, starting with President Bush, if you did anything even slightly political, you would immediately split the audience in half. It really threw us because America has such a great tradition of making fun of their presidents. Bob Hope, every year, would have a presidential making-fun-of special. But it became, “No, if you do that, you’re not a patriot.” There’s nothing worse than being told, “You can’t do this,” because it’s always in the forefront of your mind. When we’re improvising, like in the past four years, a Trump thing would come to mind and I couldn’t say it and I’d think, (in a soft, dejected tone) “Oh…”

You’ve been doing improv forever—

That’s literally true (chuckles).

If we were to speak more recently, what would you say that you’ve learned about improvising or about yourself that you didn’t catch earlier on? Like, what have you learned in the past five or ten years?

I think just having a total trust in myself. When you first start out, you’re just so excited to be on stage and you’re totally fearless, doing anything for a laugh. Which I’ll still do because I’m a laugh whore (chuckling), to put it politely. And then after a while, there’s a danger in getting too comfortable, and falling back on stuff you may have done before because you know it’ll make people laugh and get you out of a situation. Now I’m at a point where—and I don’t know if this is just age—I don’t care. I trust myself to go out on stage with Brad, or whoever, with absolutely nothing and there’s an 80% chance it’s gonna work out. And the 20% that doesn’t work out, it’s not gonna kill me. In fact, it will make me stronger.

Recently, before [the pandemic] happened, I was doing a show with a hypnotist. He had contacted my agent Asad Mecci and he said, “I have this idea where I would hypnotize audience members and you would improvise with them.” And I thought, “Oh, that sounds terrifying. (pauses). Okay, let’s try it.” Our first shows were at the Edinburgh [Fringe] Festival, and it’s a show you can’t rehearse, obviously. Five minutes before the show, I turned to Asad and said, “Oh, I probably should’ve asked you this months before, but if I ask someone to do something, will they do it?” And he said, “I don’t know, it depends on the subject. They might, they might not.” So five minutes before that show, I was thinking, “How is this going to work? What have I gotten myself into? I’m working with people who I’ve just met who are in a hypnotized state. I have no idea how much they will give me.”

So the first couple of shows—and it’s still terrifying even though we’ve been doing it for a couple years—I felt that I had to do everything. And then I realized that I had to give them more credit because they’d actually give me stuff. And then it got to the point where, by the end, I was not the main attraction of the show. These hypnotized improvisers… every night we’d find this amazing star. It was so much fun to see that build. To not know what would happen every night got me so pumped up for the artform again.

Wow, that’s all amazing. I gotta see a show. Speaking of improvising and it being revitalized for you, obviously you’ve worked with Brad for a long time, and have worked specifically with him in your shows together. I wanted to ask, what do you feel like he provides that you can’t, and what do you feel like you can provide that he can’t?

He’s very verbal. He and Greg Proops have the biggest vocabularies on our show. They’re both very smart and have interests in everything, so he knows a little about everything and uses his big words all the time. I’m more, hmm… what would be the word. I’m more, I guess, surreal? A lot of times I have more surreal moments that have no basis in reality whatsoever that we both find amusing.

This will be our 18th year of doing the show and we have such a great relationship on and off stage and I love the fact that we still don’t know what the other person is going to do. I tend to be more physical but not as much anymore—I’m 62. I tend to be wackier and he’s really good with narrative and keeping the scenes on the straight and narrow, or as straight and narrow as they can be in improv. So we each have our strengths. What I love about touring with him is that he’s a little OCD. He’s a detail guy. Things I would never think of, he does, which makes the tour better. And I’m just there to make sure he doesn’t have a stroke.

What sort of things does he take care of?

Travel things. Like, “Oh, wouldn’t it be better if we landed at this airport because then the drive to the next place we’re going would be 45 minutes shorter and we would be able to relax before the show” whereas I would go, “Oh, yeah, that’s fine.” He takes care of lights and he does all the things that I, frankly, don’t really care about (chuckles). But it makes the show better! He’ll go, “Could we have a little more peach in this?” and if someone told me there was more peach in the lighting, I wouldn’t know. It’s all those details.

You complement each other, it’s really nice.

It takes a lot of stress away. Well, at least for me (chuckling).

So I guess we should talk about the movie [Boys vs. Girls].

Oh god, yes.

Did you go to summer camps at all growing up?

I did not. It was not a thing for me. My daughter went to a camp just outside of Toronto. It was an arts camp and it was lovely. She’s still friends with… I think everyone she was there with. She became a counselor. When I would see her at the camp and see her come back, I would think, “I think I really missed something. It would’ve been really good to have had that camp experience.” I was a very shy and quiet child. I saw Kinley really bloom in that environment. I thought, “I could’ve been a better person.” Oh well. Thanks mom, thanks dad (laughter).

Did you do any preparation at all for your role in this film?

My character is the harried camp director, and basically that’s my life (laughter). I’m just playing a lesser version of myself. It was all there in the script. And with all the young people I was with, it just made it easy. The movie Meatballs, which I guess would be one of the top camp movies—my one friend played in it. He played the guy who at the end is racing Chris Makepeace. I’ve seen that movie so many times, and with him there’d be so many special screenings and we’d go.

None of the characters in that movie was something I could base my character on. I’m nothing like Bill Murray in the movie. Maybe Harvey Atkin’s character—he’s a little beleaguered in that. A lot of my acting is almost improv-based in that I do a little research if I have to, and I certainly think of my character before I do it, but a lot of it is playing off what the actors are giving me with the foundation I’ve come up with.

You said that you were playing a version of yourself. Can you expand on that? How is what you portray in the film similar to you in real life?

There are times where, to make my life better (chuckling), I try to keep everything on an even keel with people. I try to work things out and just get so frustrated that I don’t get… (pauses). When I do mad in my real life, I do funny mad. I guess I have to go into analysis to figure out why I can’t actually show real anger to those who deserve it. Maybe it’s the Scottish thing where I just get dark and sarcastic, and there are some elements of that in my character.

What does funny mad look like for you?

John Cleese does very funny mad. In Fawlty Towers, one of the funniest things for me was when his car breaks down and he leaves the frame. It’s just his car in the middle of the street, and he comes running back with a tree branch and just starts hitting it. It’s one of the funniest things because you just feel the frustration that he has and it’s all at a boiling point. He’s one of my favorite funny-mad guys.

What does it look like in real life, though?

It doesn’t get the same point across that real anger does (laughter). You really shouldn’t get laughs when you’re being angry with someone, but I feel it sort of diffuses the situation while showing that I’m being frustrated.

That makes a lot of sense. Earlier you said that you were working with a lot of younger people on the film. What’s it like being in an environment where you’re one of the oldest people around?

That’s pretty much every environment I’m in now, so I’m really getting used to it (chuckling). I work with a lot of younger improv companies, and there are a lot of younger improvisers I don’t know. It makes me go back to the basics of what improv is. It’s really an ensemble thing even though it’s called “A Night with Colin Mochrie.” Of course I’m gonna be the funniest—it’s what I do (chuckling). But I’m also not there to showboat. I’m there to do what I’m supposed to do, which is to work in an ensemble—you try to make the other person look good. And I like working with improvisers I don’t know because it makes me go back to the basics of listening, of accepting their ideas and building them up.

It’s the same working with young actors. I mean, the young actors in this movie have extensive resumes—they have worked a lot—so I can still learn from them. Something I’ve found as a 62-year-old man is that I still don’t know everything (chuckles). I can still learn from other people. I’ll watch and be like, “Oh, they just made a great choice and it was really simple.” I find that the young people I work with in movie and television are so different from young people I knew growing up. Now they have this confidence, they’re centered, they’re focused on what their job is. So you can still learn. (in a stern voice) You can still learn, Joshua! (laughter).

Oh, yeah. I’m always of the mindset there’s always more room to grow and learn. And I think that’s what makes life fun—you never reach an endpoint.

Right, yeah. And because everyone is so different, you relate to people in different ways. There are some people you’re immediately comfortable with, and there are some people you might not be so comfortable with, so you try to figure out how you can be comfortable with them. What’s the thing that’s making us not be the best we can be?

When I was at Second City, there was an actor there, Patrick McKenna, who is one of my best friends. We really enjoyed each other and found each other really funny, but when we were on stage, it just wasn’t working. It took us two months to realize that it was because we were being too polite to each other on stage. We were letting the other person go ahead. Once we got rid of that, it was magic. We were relaxed and it was so much fun and the scenes were better. You could easily move that to offstage relationships too.

Do you feel like your time improvising has made a considerable impact on the way you relate to people in real life?

Yeah. It’s certainly made me open to everything, including my daughter’s transition. I’ve learned in my years of improvising to not come in with preconceived ideas, whether on stage or when meeting someone. Maybe I’ve heard things about someone—I disregard that and go, no, I’m just gonna meet this person and make my own decision. Everyone has different reactions to different people and that reaction may not be your reaction. So, I tend to be more open, and hopefully I can keep that going.

Earlier you said that your daughter would always be looking out for people. And it’s funny because it sounded like you were saying the same thing about yourself with improv.

I’ve been incredibly lucky… incredibly lucky (chuckling). When I meet improvisers, they say, “How can we become famous.” I say, “Okay, you’re gonna hate this answer, but I just happened to be in the right place at the right time. That’s it.” The fact that a show came along that showcased my one skill is so beyond lucky. I’m making a living doing something that wasn’t a job when I was growing up. It didn’t exist. I’ve been incredibly fortunate. Brad’s always fond of saying, “There are more people who have been on the moon than are improvisers making a living.” (laughter). It’s kind of true.

I truly believe in paying it forward because, who knows, maybe another Whose Line comes along. I’ve met so many improvisers from around the world who are as good or better than any of us. Everyone on the show is really aware of how lucky we are that Whose Line came along and gave us this career.

I know we’re coming down to the end of our time—

What! Never say that to a 62-year-old man (laughter).

There’s a question that I like to ask people that I wanted to ask you. What’s something that you love about yourself?

Oh, man. You ask tough questions. Okay, let me go into myself and think. (pauses). The thing I like about myself is that I am aware of who and what I am. I’ve worked with a lot of people and people usually come up and go, “It was really lovely working with you, you’re really nice.” And my thing is, I have nothing to be a dick about. As I say, I’m incredibly lucky and I have a wonderful family. I love my job, but that’s not what defines me—that’s my job.

The personal Colin is a different person. My wife calls the guy on Whose Line “the other” because it’s so not me. I tend to be very quiet and she’s the storyteller in the family. She’s the actual funny one, and is a talented writer and improviser and actress. As I say, I just lucked out. I know that. And I don’t have a false modesty—I know what I do well. I know I’m a good improviser. But yeah, that’s it. I do my job well and that’s what you’re supposed to do when you have a job. So there.

Is there something about yourself that you’d be comfortable sharing? Like, who is the real Colin? Who is the non-“other” Colin?

There was a neighbor across the street who would get mad at me all the time because they’d say “Hi” and I’d go “Hi.” They didn’t understand why I didn’t go over there and do jokes for them or something. I think I always disappoint people when they meet me because I’m not wacky. I would not have been married 32 years if that was my offstage persona (laughter).

My perfect day is to just be at home with my family. I do all the cooking. My wife has recently developed gluten problems and my daughter is a pescatarian so I have to come up with three different meals at least twice a day, and that to me is heaven. I get up in the morning, I check my recipes and look for new things on the internet. I wake up at like 5 in the morning to pee—is this too much? (laughter).

No, it’s good!

I wake up at 5 and the first thing is, “What am I gonna make for dinner?” And that’s me for the rest of the morning because I’m immediately in “what am I gonna cook” mode. “I’m gonna have a soup today! Ooh, what am I gonna have in it!” It’s really sad in many ways.

No, no! It’s great. Cooking is one of the greatest things anyone could do. I always say that food is the best artform.

I love food so much.

What are you planning to cook tonight?

Because I have limited time today, we’re doing big salads. My wife will have a salade niçoise. Kinley will have a pesto pasta with vegetables and shrimp. And I’ll just have a big salad. I’m really looking forward to the turkey dinner because I love that. If I could I’d have that every day until I got sick of it.

Do you have a go-to recipe that you whip out when you try to impress people?

My turkey is probably my best. It’s a brown sugar spice turkey with a chestnut and leek stuffing. There’s mashed potatoes… god, now I’m just getting hungry (chuckling). [Note: Colin sent this recipe after the interview].

Do you have anything that you wanted to say or have been wanting to talk about in an interview that you haven’t?

Oh boy, what have we covered… (pauses). I hope people find a way to come together. I wish there was a program that, in school, for a month you would send your whole class to another country just so you could get a feel for what it’s like elsewhere. There’s different customs and different things, but again, we’re all kind of the same.

With this pandemic, it was the first time in my life where the entire world was suffering from the same thing, and everyone—well not everyone—but a lot of people pulled together to help each other. On my street, everyone was making sure the most senior members were taken care of, people were doing their shopping. I would hope that makes people realize that we’re all in this together. We all want the same things. We all want to be happy. We want to find love. We want to find success, whatever that is. I wish people would expand their minds more and get back to empathy. We don’t try to put ourselves in other people’s shoes as much as we should. So Joshua, fix that (laughter).

Thank you for reading the ninth issue of Tune Glue. Let’s get back to empathy.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tune Glue is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tune Glue will be able to publish issues more frequently.