015: Sophy Romvari

An interview with director Sophy Romvari, whose 'Still Processing' played at the inaugural Prismatic Ground festival and whose 'Remembrance of József Romvári' plays at this year's Hot Docs fest

Welcome to Tune Glue, a newsletter that’s run in conjunction with Tone Glow. While the latter is dedicated to presenting interviews and reviews related to experimental music, Tune Glue is a space for interviews with artists of any kind. These interviews could be with filmmakers, video game designers, perfumers, or musicians who aren’t aligned with what Tone Glow typically covers. Thanks for reading.

Sophy Romvari

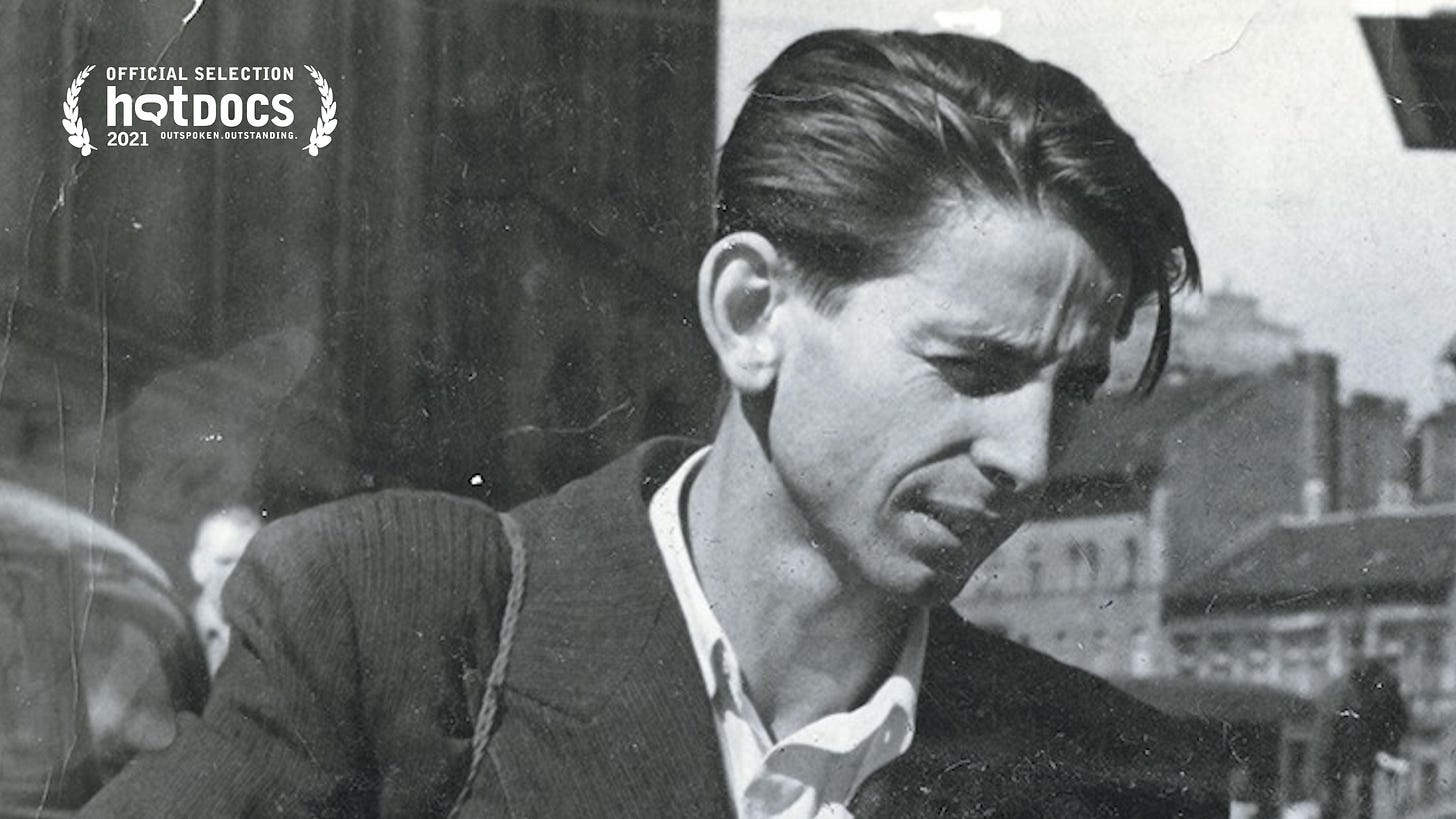

Sophy Romvari is a filmmaker born in Victoria, B.C. and based in Toronto. Her critically-acclaimed short films, many of which are at least semi-autobiographical, depict the surrounding emotions, questions, and intimacies that arise when people connect with others—pets, friends, family members. Romvari’s Still Processing follows her as she opens a box of old family photos, grieving over and thinking about the passing of her two older brothers, among other things. Her newest short film, Remembrance of József Romvari, is playing at this year’s edition of Hot Docs. The film is a portrait of her grandfather—a prolific production designer in Hungary—who Romvari never knew closely. Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Romvari on April 9th, 2021 to discuss her filmography, the new shorts program she’s working on called Exquisite Shorts, and more.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hey, how’s your day been?

Sophy Romvari: I’ve mostly been watching films from Prismatic [Ground] to be honest.

Any highlights? I watched like a bunch throughout the past couple of weeks. Were there any that stood out to you?

Yeah, I saw that you watched like 50 or something crazy. That’s an impressive number.

Yeah, in the past few months I’ve been in an intense film-watching mode. Every now and then I’ll completely stop watching films for a stretch of like six months, and then for another six months I’ll just watch as many as I can and lose sleep because of that.

That’s funny. I feel like this festival is a good way to do that, because it’s just so accessible. So you can just like click on things and watch forever.

Yeah, exactly.

You had links I guess, too. So that makes it easy. I’m just opening my Letterboxd to see what I saw because I don’t remember what I watched. I watched almost all of Wave One so far. I really liked the Anita Thatcher films.

Yeah. They were so good.

I don’t know the titles of any of them because they all just washed over me. I don’t know which one was which. I really liked [Bill Morrison’s] Curly Takes a Bath by the Sea. What else… I think my favorite so far might be, ironically because of the title, My Favorite Software is Being Here [by Alison Nguyen].

And that one stylistically just stands out, too, in comparison to everything else in the fest.

Definitely. I watched it kind of late at night, so I was in a really good mental state for it.

I wanted to start off by asking where you were born.

I was born in Victoria, which is on Vancouver island, BC. It’s a small island off the coast of Vancouver. Actually, it’s quite large.

When you think about growing up there, what sort of things come to mind immediately? What it was like for you?

So I was born in Victoria, which is on Vancouver Island, but for the first five or six years of my life I lived on a smaller island just off of Vancouver Island called Gabriola. That one is very tiny. I grew up there with my mom and my dad and my three brothers. That was kind of all the people that I saw for the first five or six years. There was one family that we were friends with, but for the most part, we were pretty much a unit, as a family.

So, my first five or six years were quite isolated from society in a lot of ways. We lived in a house that my dad built by himself and it was surrounded by forests. It was an idyllic nature setting for a small family to be around but, you know, maybe not sustainable long-term, so we ended up moving to Vancouver Island. I don’t think [Gabriola] had a high school on it, so when my oldest brother Jonathan was starting high school, we relocated to Vancouver Island. A lot of my memories from that time are very hazy, so seeing photographs and videos from that time is very helpful in order to really remember that time.

With [your film] Still Processing, you got your parent’s blessing [to make it]. I wanted you to talk a bit about your parents. Do you feel like you are similar to either of your parents at all? Do you feel like you’ve “inherited” personality traits from them or act similarly to them in any way?

I think I’m probably a pretty good mix of the two. (pause). My parents immigrated together from Hungary. My brothers were all born in Hungary, actually. I’m the only person in my family that was born in Canada. I always felt a little bit like an outsider from the rest of my family; I was more Canadian, but still not as Canadian as most people because of my upbringing. That immediately kind of made me stand out from the rest of my family.

My parents are both artistically inclined people, so there was never any problem with me going into the arts or into film, which was nice. But they also are very, uh, untraditional and unconventional in a lot of ways. It’s hard to say what, from that, has rubbed off [on me]. I think I would say it’s fair to say there’s a little bit of both of them in me.

How were they unconventional?

My parents didn’t bring Hungarian culture, in a traditional sense, with them when they immigrated. I spoke the language until I was about five or six, a similar timeframe to when we moved from [Gabriola to Vancouver Island], but then I started to speak a sort of mix of Hungarian and English. We weren’t particularly steeped in that culture, but they also didn’t really assimilate into Canadian or Western culture. So I think we landed in some sort of middle ground where it was just our own bubble, our own unit. Most of my understanding of Western culture or the people around me was from going to friends’ houses and being in school. That’s how I was able to understand what was normal and what was not normal (laughs). You know, we did do things like Christmas and things like that, but they weren’t very committed to more classical traditions

That’s similar to my family. My parents immigrated to America from Korea when they were 18. And then, similarly, there was an assimilationist sort of mindset, unintentionally, because they just didn’t want to do various Korean cultural things within the household. I think a lot of their memories of Korea are negative. But then at the same time, they spoke Korean. I spoke Korean when I was younger, but I’ve definitely lost it. So I totally get that.

Immigrant parents, when they have their children in a new country or they bring young children to a new country—that’s a pretty pivotal decision [they have to make]. And I think it’s a very personal decision. I do wish I spoke Hungarian now, but I can understand from their point of view… it’s not like Hungarian is like French or Spanish—it’s not a super common language. I don’t think they thought it was going to be super useful, but of course now I wish I was bilingual.

Given that your dad was a cinematographer and your mom was an actress, did you grow up seeing Hungarian films in your household?

I didn’t grow up seeing Hungarian films specifically, but we did watch a lot of movies and I think it wasn’t until much later, like my late teens, early twenties, that I started to really pay attention. My dad would show me films at a younger age and I would just be a bratty teen about it. Recently I posted on Twitter that I had just watched The 400 Blows for the first time and then my dad said, “I’m pretty sure I showed you that when you were a teenager” (laughter). I wasn’t paying attention. My parents are definitely cinephiles to a certain extent. They have Mubi and Criterion and they still watch a lot of movies.

Do you recall the initial films that sort of made you realize that you wanted to go into filmmaking, or maybe like the conversations that you had with people about film that made you realize that?

I don’t think there’s one particular film. I think it was just the experience of going through my teenage years, knowing that I was interested in the arts, but not really being able to pinpoint what within the arts I was interested in. I tried a lot of different things. I really enjoyed acting, and I still enjoy acting, but more for fun. I also enjoyed painting and dance and all these different things that I had the opportunity to try because my mom put me in like a million different classes.

It wasn’t until I kind of stumbled into film that I was like, “Oh, this is the right one. This is the one that combines all of these different things.” As soon as I started making films and getting obsessed with watching films, it was like a switch went on and never went back off. I have had lots of doubts, but I’ve never had a doubt that this is what I want to be doing.

It’s totally crazy. Once in a while, when I have those doubts, it’s less, “Should I be a filmmaker?” and more “Oh, I guess I have to be a filmmaker.” It’s just obvious, in my mind, in my own experience. [It’s] what I’m just so drawn to now that I can’t really imagine anything else. But I dunno, I kind of hope I do something else, as well, on top of filmmaking. As much as I’m passionate about filmmaking, I can’t totally imagine myself only ever making films.

The doubts that arise when you are following your passion are always gonna be there. ’Cause it’s sort of a crazy thing to be following your passion, I think, in general.

Yeah (laughs). Yes.

What’s something that you’re interested in outside of film that someone who is familiar with your movies would not know about?

In an alternate universe, I could have seen myself going into social work. That’s something I’m planning to explore in my work, actually. I think there’s definitely a part of me that gets concerned with the self-absorption that comes with making films, whether you’re making films about yourself or anything, you’re still fixated on your own point of view and your own perspective. Not that there’s anything wrong with that—it’s just that I sometimes get the sense that I would rather be exerting that energy towards things that can actually manifest more tangible change or help people that need it.

You know, I do believe that art and film are significant sources of help to people, but I don’t totally buy that they’re on par with people who are really doing the work that actually creates change in people’s lives. And I think it’s something that’s more easily done if you have the means and the stability to do those things. That’s part of my plan, when I have more stability that I can put that energy toward other aspects. I’m starting a shorts program called Exquisite Shorts and I’m hoping to really channel some energy into that and make it into a community space for filmmakers. That will be good to put my energy toward.

The thing that you said, regarding not being fixated on your own point of view—I’m wondering, are there things that you do in your own life, whether it’s regarding filmmaking or not, that you do to have that mindset of thinking about others more regularly?

I think that’s partly where the idea to start Exquisite Shorts came from. I felt like I was talking to other filmmakers that were struggling with pretty common issues within the film industry. So I spent a lot of time talking about those issues and it dawned on me that I was in a position to actually do something about it. I was able to fundraise a small budget for the project and now I’ll be able to pay other filmmakers to show their work. And that’s just a small way that I can give back to other filmmakers.

With your experience in the film world, what are you trying to bring to Exquisite Shorts that is going to keep it community-oriented, in comparison to other things you’ve seen? Do you feel like that community-oriented mindset is present in the film world anywhere?

All very good questions. To be honest, I think that with this festival [Prismatic Ground] that Inney [Prakash] put together is a really good example of how to make film exhibition community-oriented and accessible. I think it’s a perfect example of a festival, particularly an online festival, that is trying to address those questions. It’s really nice to see examples of that coming up, especially being born out of this disaster of a year. With Exquisite Shorts, the emphasis is to give filmmakers a space to program work, rather than have curators or programmers program work. I think they’re just very different perspectives. The program is going to focus on what filmmakers find interesting or inspiring, films that they want to give a platform to. That in and of itself will create a discourse because, as a filmmaker, you’ll be programming another filmmaker’s work. And then those two filmmakers will be in discussion. And then following that, the next filmmaker. So there’ll be a chain of filmmakers that are meeting each other [by] curating each other’s work. I’m really curious to see how that plays out.

It’s less about curating the best of the best work or work that is thematically linked. I understand all the issues that some festivals have to answer to: sponsorship and having programs that are audience-friendly or engaging for their particular brand. There are so many reasons why film festivals do the things that they do. So that’s why it’s nice if you can create alternatives that are not stuck or bound by those issues or conventions, like Inney’s doing.

The fact that he was able to create a program that is free and available to everybody and is paying filmmakers is crazy. But it’s also crazy to me that it is crazy. That’s a big part of the reason I fundraised, so that I could pay screening fees to filmmakers because I find it absurd that in film it’s more common to not get paid to show your work than it is to get paid. There are very few other arts or jobs where that’s the case, where they’re just going to pay you in exposure or whatever.

I think about Another Gaze’s Another Screen programming and how those are free, how they have subtitles in multiple languages, how there’s good descriptions and conversations about films as accompanying text. I’m just like, oh my gosh, I wish it was always like this.

It shows people’s priorities, for sure. I think this last year has been really illuminating for some festivals showing their cards more than others. For example, Camden Film Festival, a great non-fiction film festival, decided to do a revenue share with their filmmakers. They’re offering their filmmakers a portion of whatever they make because that’s logical—your filmmakers are giving you their product. There’s huge amounts of value in having exposure for sure, but that’s not really a fair trade.

I also only know things from the short film side of things. My perspective is honestly that there should be more financial support for shorts filmmakers. Particularly because shorts filmmakers are more often marginalized people who can’t afford to make a feature and are trying to figure out what their voice is, and so if people are talking about wanting to support diverse filmmakers, then support shorts filmmakers! That’s how they’re going to be able to make a feature, if you financially subsidize their work.

I think about the fees that are present when you’re submitting something to a festival, and how everyone knows that for the most part, the majority of films that are going to be shown are by people who are already established.

Absolutely. You’re basically subsidizing the festival with your submission fee in most cases. So you can spend hundreds and hundreds of dollars submitting your films and the same like 20 films will play festivals all year or whatever.

This is something I’ve been thinking about a lot the past year. I run my own publication and, for me, what’s most important is understanding that this is something that’s beyond just a publication—it’s also a community of writers. A good chunk of these writers aren’t established, and some hadn’t really written before joining, plus a good amount of them are people of color and/or queer. And while they lacked experience, they’re still great writers or end up being great writers.

Someone once asked me, “Why are you doing this when you could just be getting the best people and have the best possible content.” That’s the sort of trade-off we always have to ask ourselves when we do these things, right? Do we care about community enough to understand that it might not be the very best thing in the world right away? The reality is if we only [aim for] that, then we’re never going to be supporting people who are typically marginalized, because they haven’t had the experience to fail. They haven’t had the experience to be mediocre in order to get better.

I think that’s a really good point because with curation, the idea is to try to find the best, but the best is already a subjective thing. I think that there’s enough places that are subjectively curating work. So why not have spaces that are, you know, their mandates are not in line with, “What is ‘the best’?” They have alternate reasons for supporting work, other than quality, because quality is just so like… what is quality? (laughter). You’ll watch films at Sundance or whatever, and so many people are like, “Oh, Sundance movies suck.” And I’m like, they’re supposed to be the best movies in the world!

I dunno, it’s like, there is no such thing as quality when it comes to film. It’s such a personal thing, right? We’ll complain all year about how horrible the Oscar-winning films are, but that’s the ‘pinnacle’ of quality as we’ve decided on as a culture. Why are we so obsessed with quality? I hate complaining about curation, because I think curation is so important, but over time there’s this inherent power dynamic that is problematic. I think making Exquisite Shorts really helped me sympathize with that experience as a curator, but also made me realize all of its flaws at the same time.

Right. My publication focuses on music and I’ve realized it’s actually not that hard to make sure that you’re covering music from people who are not white cishet males. It’s kind of actually really easy if you just make the conscious decision to be like, “Let’s just also cover other stuff.”

I think there are things that are codified when we discuss what things are the “best.” Like, the things that are historically the best have been decided by those who are white, cishet males, and the things made by them are what’s considered the pinnacle of any artform. And sometimes, when something seems askew or something seems “bad,” it might just be because it’s different.

That’s something that I’ve been grappling with on Exquisite Shorts because part of my mandate is that I want anyone to be able to submit their work. I want it to be truly a blind submission process, rather than having a pool of submissions that are curated already. The way the program works is that anyone can submit their work. The filmmaker who is deciding will pick from those submissions. What I’ve been really struggling with is how to encourage people to select work that is by diverse filmmakers without just being like, “White men can’t submit their work.” (laughter). I’m not going to do that. I really want it to be an open process for everyone to be able to engage in.

There are pitfalls of trying to do too much, of trying to establish too many different standards with it. I’m putting faith into the program and hoping that people will make those choices by virtue of the cultural moment that we’re living in. And hopefully we’ll continue to live in it and people will seek out work that is different. It’s very complicated to try to find the right way to do it without minimizing people into their identity at the same time. It’s a tough balance to find.

Right. You want to be mindful of these things, but you don’t want to put them in the box. It’s always very upsetting when I get an email for a new artist and the email subject line has stuff about their identity when their art doesn’t really end up being explicitly about it. It becomes very reductive.

I’m interested in seeing what other artists are interested in, and I’m asking people to include an artist statement when they submit their work. So along with the submission, you’re going to see a bit of why they made that work and what it means to them to try to give people a decent picture of the context beyond the work or beyond a filmmaker. But it’s so easy to make missteps that are not in line with what I want. There’s an element of control that I have to let go of.

I asked Isabel Sandoval to pick the first film in the program, but after that, I’ll never have anything to do with the curation again besides logistics. I’m not curating or doing anything to filter what’s happening there. I’m gonna take a glance at every film that gets submitted just to make sure there’s nothing horrific but, other than that, I want it to be a purely open submission. Which, I don’t know if that exists and there’s good reasons for that. (laughter). I keep forgetting that I can kind of adjust as I go. Once it’s launched, I can make those adjustments if it’s not working or if something’s not feeling right. But yeah, I didn’t really intend to start a company, but I guess...

That’s what happened.

Yeah. It’s not a company. It’s a… what is it…

Sophy, LLC.

(laughs). It’s just a website.

Are you the sort of person who finds it easy to let go of control?

(pauses). (quietly) Is this a therapy session?

Oh, sorry. I can totally not ask these kinds of things.

No, I’m kidding. Film is a great medium for anyone who likes to control their surroundings because you get to control everything that’s on screen (laughter). I don’t know. It’s a good question you ask. I guess it depends on what aspect of life. I feel like I’m a go-with-the-flow kind of person. I don’t have a very rigid lifestyle, so maybe not.

I was reading an interview you had regarding Still Processing and I liked how you said that you had an “emotional collaboration” with your parents. I like that phrase. Is that something you try to ensure exists whenever you’re making a film? You had In Dog Years, where you’re trying to build an emotional collaboration with the people you were with, and then there’s Some Kind of Connection. How much of that is something you think about when you’re making films?

Most of my shorts are pretty emotion-based. I really try to focus on, or simplify, emotions in my work to channel into a very specific one. I would say that I rely heavily on my instincts, which I guess are in relationship to emotions. My intuition and my instincts are very strong when it comes to filmmaking. Maybe less so with my daily life (laughter). It’s very strong in my work and I don’t know why that is. I feel very confident about the decisions I make, but then I’m still a work in progress in other areas of confidence.

In your filmography, are there any films where, after making it, you recognized how much you had grown as a filmmaker?

I guess there’s two examples, one being Nine Behind. Then also this last year getting to make the film about my grandpa, [Remembrance of József Romvari]. Nine Behind was about this fictional conversation I had with my grandpa. And then I felt like I got to fill those spaces with Remembrance. So I did grow as a filmmaker, but also as a person in that time. I learned more about that connection and what it meant in relationship to my own life and career. I definitely can see the searching I was doing in Nine Behind as a very young and curious filmmaker, and then I can see much more confidence and assuredness in my most recent film.

Similarly with It’s Him and Still Processing. In It’s Him, I was playing with a much more fictionalized version of some of the elements of Still Processing, and there were certain things I wasn’t really willing to, or I was too afraid to talk about. [It’s Him] is a very elusive, vague film. I have a fondness for it, but I think watching Still Processing now, I think anyone who sees the two [together] can be like, oh, that’s what she was talking about. I wasn’t really ready to make that leap and then, in Still Processing, I did. I’m still withholding about certain elements, but I was much more able to, and ready to, tell that story. It’s only stuff I notice in retrospect though. It’s not like I made those films knowing I would grow into the person I am now. You don’t realize what you’re even getting at until years later.

I like your films because they capture my favorite thing about any sort of art, which is that it becomes a conduit for doing other things. When I watch your films, I can tell that the act of making it was an important process. I don’t know if you necessarily had the intentions laid out before you made the film, but my impression—and maybe this is me projecting—is that these films granted you the boldness to do and process things that maybe you wouldn’t have been able to do otherwise.

All of my shorts were in some way necessary for me to make. I never was confident that they would be necessary for anyone else to watch (laughter) until after. You know, in most cases with my work, I finish it and I’m kind of like, is that a film? And I show people and they’re like, “Yes, Sophy, that is a film.” And it’s truly because I think it’s such an instinctual, emotional, personal whirlwind of things happening, and I’m so sure of what it is that I’m making, but when I finish it, I’m like, “Does this make sense to literally anybody else?” And then it’s not until I start showing people that I am confident in that aspect, which has been a really satisfying way to make work, especially short-form work, because it allows me to make work without being hyper-aware of the outcome and how it will land with other people.

Now that I’m trying to transition into feature filmmaking, that’s less applicable. There is inherently more planning with a fiction film or a feature film. You can’t just go into it with a storm of emotions (laughter). I mean, you can in smaller pieces, but I’m trying to translate my short form process into something more sustainable.

Do you know what sort of things you want to tackle with your feature film? Do you have any ideas for what it’s going to be about?

I am writing a script right now. I’m not totally ready to talk about it yet. It’s definitely a much more fiction-based film. But there are definitely autobiographical elements to the story, so it feels like a natural next step, I think.

Your latest short, [Remembrance of József Romvari], is going to be playing at Hot Docs. That film is about your grandpa. I’m curious what that process was like. Had you seen the films that he had worked on prior to getting ready to make that film?

Surprisingly, no. I had put it off forever because I always thought I had to be in the right headspace to really dive into that. I knew it was going to be kind of emotional for me. I live in this bizarre contradiction where I have this grandfather who was working in the exact field I’m in, in a really prolific and high-achieving way that I had no access to. I think most people who are in that position, it would be pretty clear the way that would affect them as a filmmaker, but in my case, it wasn’t really that way. Watching his work for me does bring about some feelings of what could have been.

Seeing and learning about how he was as an artist is really meaningful to me. I do feel that connection, but at the same time, I didn’t really get a chance to explore it while he was alive. So making this film forced me to reckon with that So, another film of Sophy reckoning with her past (laughter).

Was it a scary thing for you to do initially, to put yourself out there and depict yourself grappling with various aspects of your life?

Yeah, it’s terrifying. I mean, I am a pretty vulnerable person, that’s something that I think comes quite naturally to me, but that does not protect me from being hurt. Putting work out like this, I am really trusting that the audience will understand where I’m coming from. And I feel like with Still Processing, in particular, I’ve been unbelievably lucky with the response. Every time I read someone’s thoughts or view on it, where they’re just pouring out their own emotions or their own experience, it’s just such a huge relief. Putting something out there like this, I wouldn’t be surprised if people didn’t take to it very well. I don’t like to classify it myself, but I know that for some people it’s a lot.

It’s also been a bizarre experience making this film and then sending it out into the world, and never getting to see anyone react to it in person. Sometimes I’ll play a festival and I literally don’t hear from anybody, I don’t know if anyone watched it or if they liked it or how they felt about it. It’s a very weird experience because when you’re actually at a festival, even if you don’t talk to anyone, you get a sense of the room.

The atmosphere.

Yeah, exactly. So I think it’s been a bit of a blessing and a curse because I couldn’t really imagine myself traveling around with this film. It probably would be traumatizing. Just very exhausting. And I have been warned by other filmmakers who made personal work about putting yourself in too many positions where you have to do Q&As for a work like this, it can become really draining. So in this way, people can kind of experience it on their own and react to it personally, if they want to. And that’s worked out quite well, actually.

This distant setting might be good for the audience too, because then they can sort of feel free to respond to it.

I think that actually has worked out. I do hope I get that experience eventually, to see it with an audience, but I don’t need to see it 20 times or whatever. But yeah, [putting myself out there] is absolutely scary. And every time it has a bigger audience, I’m always like, oh, now here comes the hammer. It’s gonna come down. Someone’s gonna call me a phony or, someone’s gonna, you know, say something awful and just break me.

It’s funny, you saying this, because I think so many of your films reveal the importance and the beauty of connecting with people, whether it’s through memories or in person or through rituals, like with Pumpkin Movie. That’s a really big takeaway for me from watching your films. It’s obvious how much you value these relationships that you have with people. It’s an encouragement for me to make sure I’m prioritizing those things in my own life.

I’m really into art in general and I think it’s easy to get sucked into that world and just care about the art itself, to the point where I box myself out from caring about others. I’ve been trying to shift gears the past few years and seeing your work sort of was a nice affirmation because it’s so embedded into your films. And I guess to turn this into a question instead of a ramble…

(laughs). That’s very nice though. Thank you.

Do you mind sharing a ritual that you have with a friend? Just one that means a lot to you, and it could be the smallest of things.

So in Pumpkin Movie, Leah, who plays opposite me, is very much my real-life best friend. The ritual itself was fictionalized, but that was a pretty candid depiction of our friendship. She’s one of those friends that I can get together with after not seeing her for months or even years and it kind of falls back into place. We went to high school together and I’ve known her since I was like 12 or 13. She’s a friend that I can really depend on. She has a better understanding of who I am than almost I do. She is really good at bringing me back to myself. Every time I see her, I feel more myself than I have, you know, previous weeks or months without her.

Wow.

I feel like when we spend a significant amount of time together, it’s like I get recharged or refueled and then I’m back to Sophy 100%.

What a beautiful thing to say about a friend! Like, could anyone say anything better? It’s a legit blessing to have someone in your life who can make you feel most like yourself. I’m really happy for you.

It is a huge blessing. And I think the funny thing is, I think she is that person for a lot of people. I know she is that for me and I know that, in a lot of ways, I am that for her too, but she has such a giving energy. It’s really special and grounding. I can get really caught up in the drama of my own life or things happening on Twitter, or whatever, and she’s always able to slash that to bits. “That’s dumb, you’re great.”

She’s really funny. She knows people on Film Twitter and stuff now, too. I brought her with me to True/False, the festival where Pumpkin Movie premiered and she like (thumps table) dropped right into the film scene and was friends with all these big critics and filmmakers within five minutes.

I had one more question but, before I ask, I was wondering, is there anything that you wanted to talk about in an interview that has not been brought up before?

I think I touched on it before, but I really want to emphasize how meaningful this experience with Prismatic has already been over the last couple of days. It’s been the experience that I feel like I’ve been the most engaged with, virtually, so far. It feels like people are really watching and talking about it and experiencing it together. And accessibility is so at the forefront of it, you just go to the website, you click on images and then movies play. It’s amazing that [Inney Prakash] managed to make it.

I saw someone compare it to just walking into an art gallery and you can just experience it as it’s set out for you. And I’m trying to walk through it, like Wave One, Wave Two, Wave Three. I haven’t even gotten to my Wave Three. Props to Wave Three! It’s really heartening to be involved in a festival that cares so much about its filmmakers. That’s obviously the priority of the festival and he’s also doing Q&As with every single filmmaker.

It’s ridiculous.

It’s really, really impressive. I was trying to think of ways that I can promote donating to it on the sly because I feel like it’s maybe weird since I’m playing at the festival, but I would like if people could donate to this festival—it’s such a worthy cause.

My last question for you is the last question I always ask everyone. Do you mind sharing one thing you love about yourself?

I really feel like I should pay you for the session, like therapy (laughs). (long pause). I love how much I love other people. Maybe this is a cheating answer, but I do. I feel like I have a very strong passion for other people, engaging with other people, learning about other people, and witnessing other people exist. And I think that’s why I like movies so much. You have such a great opportunity to do that and to witness experiences and people and cultures and things that you are not necessarily privy to. I’m just glad I love people because it’s such a big part of life. It’s such a privilege to try to do that in my own work, even if so far I’ve been quite introspective. I’m always hoping to broaden that experience more. And I try to capture things that are, you know, “universal through the specific,” to be cliché. I think I am really drawn most to work that I can connect to some kind of human element.

I think an acknowledgement of one’s own capacity to love others and the fact that you like that is a really beautiful thing. I think a lot of people would be reticent to mention that. It maybe feels like a weird thing to say, but I think the people who do are often legitimately full of love. I think that comes across in your movies, too, right? Similar to what you said about your friend, I think your films—whether it’s you talking about your grandpa or you processing things about your relationships with other people—in filming those things, you’re revealing the beauty in that relationship, which in turn reveals so much of who your subject, who that other person is.

One of my impetuses for making films is, I try to depict experiences of loneliness in a way that counteracts the loneliness and makes you feel less lonely. Being able to relate to the feeling of some sort of isolation or grief I think inherently makes you feel less lonely. When I watch movies and I see someone experiencing something similar that I’ve been through, it gives me hope or faith in my own experiences. And so that’s something I try to do. I try to really be true to my experience and I think by doing that, it does allow other people into that experience. Whenever it works and it lines up with someone else, that’s the most satisfying experience. If they can see my personal experience and I’ve left just enough gaps and spaces for them to impose their own experience onto it? For me, that’s the shit.

These are not necessarily things people want to talk or think about, but they’re maybe things that people need to do, and maybe they don’t know that unless they’re faced with it. I can’t speak to other people’s experiences. That’s why it’s so helpful to get feedback and to hear from other people. With Still Processing, I really didn’t know until I started sharing it how it was hitting other people. I really made this film for my parents, in a lot of ways. So, the fact that it was able to register for other people, regardless of if they’ve had any kind of similar experience, was really, really heartening to see just in terms of the kind of films I want to make. It really gives me a lot of hope.

How did your parents respond to the film?

So obviously, it’s in the film that there was a negotiation about even making it. That was, I think, because they didn’t really understand what it was that I was trying to do. The film is kind of unusual in that it doesn’t really divulge much information. It’s much more emotional in its tenor and visuals. They weren’t sure how it was gonna navigate those nuances, but then when I showed them the film, I sent them a link and then they called me up on Skype after. They were both in tears and they just, they loved it so much and they were so happy. And now they’re just so happy to see that it’s getting out into the world and that people are reacting to it so positively. I think a big part of what I really wanted to do with the film was help my parents deal with the stigma—which I think that they feel—of having lost children. I wanted to help them see that there is a lot of compassion and humanity that people will provide if given that information. I think it can be really scary as a parent to face. I think that the love that [Still Processing] has received has been really encouraging to them.

What a gift you can give your parents.

I mean, I needed to make that film for myself too. But I think the reason for making it was very much a gift I wanted to give them.

Information about Sophy Romvari’s films and their viewing availability can be found on her website. Her newest film, Remembrance of József Romvári, is playing at this year’s edition of the Hot Docs festival.

Thank you for reading the fifteenth issue of Tune Glue. Let’s all find and be a friend who can bring others back to 100%.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tune Glue is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tune Glue will be able to publish issues more frequently.